Interview with Faculty Fellow Javier García Liendo

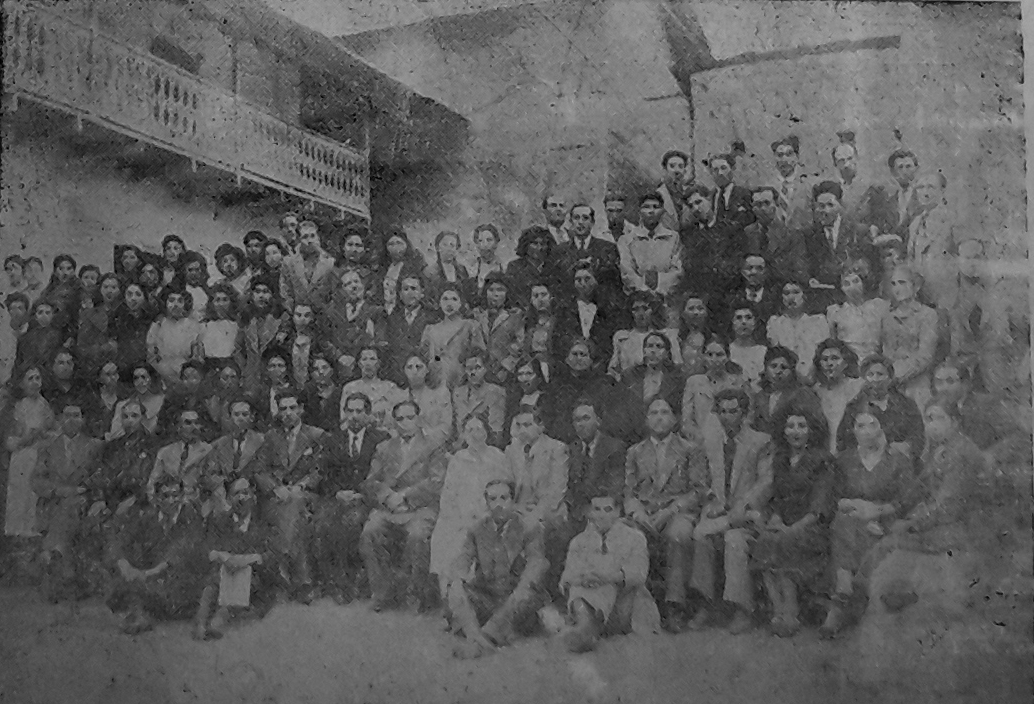

By the early 1940s, the Peruvian state knew it had a problem and an opportunity: In a country of 7 million people settled across an area twice the size of France, the biggest portion of their population lived in relatively autonomous mountain regions, and many had little connection to modern Peruvian society. “The 1940 national census— the first since 1876 — showed that little had been done to ‘integrate’ the indigenous, rural population and to exploit the country’s agricultural wealth,” says Javier García Liendo, associate professor in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and Faculty Fellow in the Center for the Humanities. “This realization resulted in sustained increases in the education budget and the proliferation of teachers’ colleges, which led to primary education and normalistas (formally trained teachers) finally reaching the most distant rural areas of the Andes.” García Liendo’s book-in-progress, “The Children of Indigenismo: Schoolteachers and the Making of Popular Modernity in Peru,” considers the role of these schoolteachers as agents of rural progress in the Andean provinces of Peru between 1939 and 1967. Here, he offers a preview of the project.

Briefly, what is your project about? What is significant about the period of time you focus on? Can you touch on the concept of indigenismo?

My project studies schoolteachers as agents of rural progress in the Andean provinces of Peru between 1939 and 1967. During this period, schooling spread rapidly to the most distant rural areas of the Andes, and the creation of more teachers colleges favored the presence of normalistas (formally trained teachers) in peasant communities and small towns. Influenced by U.S., European and Latin American pedagogical theories and Peruvian and Latin American indigenismo, normalistas brought together in their work inside and outside the classroom schooling, modernization and indigenous societies. Schoolteachers became local intellectuals, engineers, doctors, literary writers and visual artists in peasant communities and small rural towns.

Indigenismo refers to a broad set of ideas, practices and institutions concerned with the place of indigenous people within modernity. Under the banner of indigenismo, one can find a heterogenous body of social and humanistic thought, literature, arts, legislation, anthropology and so forth. In centering indigenous populations, indigenismo often reproduced racist and paternalistic views about them.